In 1943 – The First Expedition

The 77th Indian Infantry Brigade

Commander – Brigadier Charles Orde Wingate, DSO (Ex-Royal Artillery)

Brigade Major – Maj. R.B.G. Bromhead → Repl. by Maj. Gilmour M. “Gim” Anderson (Highland LI)

Staff Captain – Captain H.J. Lord (Border Regt)

13th King’s Regiment (Liverpool)

3/2nd Gurkha Rifles

2nd Burma Rifles

142nd Commando Company

Staff, The Bush Warfare School

Eight Royal Air Force Sections (to co-ordinate supply airdrops)

Brigade Signal Section (Royal Corps of Signals)

Mule Transport Company

This brigade (which used the designation of “Indian infantry” purely for deceptive purposes) deployed the field in the form of the following groups:

This brigade (which used the designation of “Indian infantry” purely for deceptive purposes) deployed the field in the form of the following groups:

No 1 (Southern) Group

CO – Lt-Col. Leigh Alexander (3/2 Gurkha Rifles) – KIA 28 Apr 1943 (by sniper).

Adjutant – Captain Birtwhistle (3/2 Gurkha Rifles)

No 1 Column – Major G. Dunlop, MC (Royal Scots)

2-i-C: Captain V Weatherall (3/2d Gurkhas)

Guerrilla Platoon (142d Company): Lt. J Watson (Black Watch) → Repl. by Lt Nealon (KOSB)

Burma Rifles (Recce Platoon): Captain M Freshnie

Medical Officer: Captain N Stocks (RAMC)

RAF Liaison Officer: Flight Lt. J Redman

No 2 Column – Major A. Emmett (3/2nd Gurkha Rifles) → Repl. by Major Burnett

No 2 (Northern) Group

CO – Lt-Col. S.A. Cooke (Lincs Regt, attached to King’s Regt)

Adjutant – Captain D. Hastings (King’s Regt)

No 3 Column – Major J. Michael Calvert (R.E.)

2-i-C: Captain G Silcock (3/2d Gurkhas)

Commando Platoon, 142d Company: Lt. Jeffrey Lockett

Burma Rifles (Recce Platoon): Captain Taffy Griffiths

Medical Officer: Captain Rao (RIAMC)

RAF Liaison Officer: Flight Lt. Robert Thompson

No 4 Column – Major R.A. Conron (3/2d Gurkha Rifles) → Repl. by Maj. Bromhead (Royal Berkshire Regt)

No 5 Column – Major Bernard E. Fergusson (Black Watch)

2-i-C: Captain J.C. Fraser

Adjutant: Lt. D.C. Menzies (Black Watch)

Commando Platoon: Lt. J.B. Harman (Gloucestershire Regt)

Burma Rifles (Detachment): Captain J.C. Fraser

Medical Officer: Captain W.S. Aird (RAMC)

RAF Liaison Officer: Flight Lt. D.J.T. Sharp

No. 7 Platoon: Lt. P.G. Stibbe (Royal Sussex)

No. 8 Platoon: Lt. J.M. Kerr (Welch Regt)

No. 9 Platoon: Lt. G. Roberts (Welch Regt)

No 7 Column – Major Ken D. Gilkes (King’s Regt)

No 8 Column – Major Walter P. “Scotty” Scott (King’s Regt)

Commando Platoon: Lt. T. Sprague

Burma Rifles (Detachment): Captain Whitehead

Medical Officer: Captain J.D.S. Heathcote (RAMC)

HQ Group (2nd Burma Rifles →This group was primarily a recce element)

CO – Lt-Col. L.G. Wheeler (Burma Rifles) – KIA 4 Apr 1943 (by sniper).

Adjutant – Captain P.C. Buchanan (Burma Rifles)

Deception Party CO – Major Gordon Jeffries

The First Expedition, Operation “Longcloth”

The story of the first expedition was inked onto paper by General Sir Archibald Wavell, the Commander-in Chief of India. At the start of 1942, as Burma brewed up in a maelstrom of war and relentless Japanese invasion, it was decided to bring in a Middle East expert to train Chang Kai-Shek’s Chinese army for guerrilla warfare. That Middle East expert was Major Charles Orde Wingate — a junior colleague well known to Wavell from his pre-war Palestine days and from wartime Ethiopia.

Following a long stopover in Cairo, Wingate finally arrived in India by B-24 Liberator, meeting Wavell on March 19. By this time, the Burmese capital, Rangoon, had already fallen and Wavell conceived a new role for his subordinate – to carry out a guerrilla war against the Japanese using British army resources. By this time four unique entities of irregulars were already conducting special operations against the enemy including the British Special Orders Executive (SOE), the American OSS (forerunners of the CIA), V-Force, run by Anglo-Burmese and Anglo-Indians with intelligence and guerrilla teams embedded in deep cover within Burma and lastly, the Bush Warfare School at Maymo busy training guerrilla soldiers under the supervision of the school commander, Major Michael Calvert.

Wingate declined on all except the Bush Warfare School which caught his fancy. Calvert later recounted his first encounter with Wingate (by now promoted to Lt-Colonel). Seeing an unfamiliar man sitting impertinently at his desk, Calvert glared. “Who are you?” he asked the stranger.

The other man gazed at him serenely. “Wingate,” he said.

“In spite of my unpleasant mood, I was impressed,” Calvert wrote later. “He showed no resentment at…[my] somewhat disrespectful treatment. He began talking quietly, asking questions…and to my surprise they were all the right questions. Tired as I was I soon realized that this was a man I could work for and follow.”

Slowly, operational ideas began to take shape. Wingate had thought deeply about the task at hand and came up with what he called “long-range penetration group” tactics, similar to the ones used by his “Gideon Force” in Ethiopia over a year earlier. He believed that a properly trained and supplied force could operate for some time behind enemy lines causing damage and disruption of the enemy’s communications, his supply lines and morale. He planned to have regular army units, properly trained for mobility that could engage in hit-and-run tactics without being constrained to conventional means of supplies or communications.

Mobility was vital, for it would allow raiders to attack whenever they desired, wherever the enemy least expected it and allowing them to withdraw without being pursued. Units would infiltrate through the jungles and ridges in small groups, to operate deep in the Japanese rear, cutting supply lines and harassing local forces. Air power played an integral part in the plan for it was meant to aid in reconnaissance, carry out supply drops and provide close air support, replacing the more traditional artillery in this role. Specially equipped RAF radio-controllers were to be attached to each of the groups.

After careful consideration, Wingate chose Burma’s central valley, where a vital railway network linked Mandalay with Myitkyina (pronounced Michenar) – the supply artery for Japanese forces in the north. In typical fashion, he ignored standard protocol and staff hierarchy, and having his staff officers’ type up the plan before presenting it directly to Wavell. With Wavell won over and backing officially confirmed, Wingate went about improving the plan and by August 1942, a training center was set up for his yet to be formed force. This was not accomplished without difficulties. In the conservative Indian Army many high-ranked officers were opposed to the creation of a special force in their midst.

One strong opponent was Lt-General William Slim of the Fourteenth Army, who later wrote that Wingate, “fanatically pursued his own purpose without regard to any other consideration or purpose.” Indeed, the bearded Wingate, suffering from eczema and frequently seen with an alarm clock dangling absurdly from the belt of his battledress, was seen more as a madman than a soldier. But on the search for his cadre, willing to think in unorthodox methods, he came across men who saw him as a genius. One was Calvert. “With his thin face, intent eyes and straggly beard, [Wingate] looked like a man of destiny; and he believed he was just that,” Calvert wrote. Others holding reservation about this new type of warfare, quickly fell to his engaging personality and willingness to experiment. Major Bernard Fergusson, an initial skeptic later said that, “Soon we had fallen under the spell of his almost hypnotic talk; and by and by we – or some of us – had lost the power of distinguishing between the feasible and fantastic.”

Even as Wingate’s strategic thinking congealed, he was deftly promoted to Brigadier in early 1943 and given command of an entire brigade (officially, the “77th Indian Infantry Brigade” ) with three full battalions — on paper, an impressive force. Reality was different. Unhappy with the quality of troops given to him, Wingate worked hard to convert them into hardened fighters accustomed to the harshness of the jungle. It was no mean task. The Englishmen of the 13th Bn, Kings Liverpool Regiment were unenthusiastic for the role thrust upon them – they were considerably older than most soldiers and too well adjusted to garrison life. The next unit – the 3/2nd Gurkha Rifles was fresh but inexperienced, and comprised some officers who were poorly trained and disliked their mission.The last unit – the 2nd Burma Rifles was in low-morale but comprised of expert soldiers from the hill tribes of Burma, such as the Kachins, Karens and Chins, who became guides and reconnaissance troops.

In order to fill out the serious short-fall of experienced troops, Wingate gladly took on the Bush Warfare School which had by then been badly gutted, losing some 100 men to a Japanese ambush at the Irrawaddy River. The eleven survivors were counted on as a cadre in Wingate’s new force as was the veteran 142nd Commando Company, specialists of all types and men trained to handle pack animals. Wingate christened his new unit, the “Chindits” after the Burmese word Chinthe, a mythical lion that guarded the Burmese stone temples.

The training slowly kicked in and began to build up the fitness, competence and confidence of his new unit. Men were pushed beyond the limits of what they thought they could endure in the jungle and the rains. Loaded with heavy packs, Wingate marched them through ruthless terrain until long marches and exhaustion became daily routine, with those passing out revived by instructors and forced to continue. Attending sick parade without a good cause became a punishable offense and orders were carried out on the run. Jungle craft was perfected to an expert level; this included teaching jungle navigation, patrolling, water discipline and marksmanship. Sickness, minor injuries and heat were inconsequential to the tough standards of Wingate, who saw the mind and willpower as the key to success.

This rigorous training and discipline was essential, for the troops would soon find themselves operating without regular supply or medical aid deep behind enemy lines. In due course, instructors ruthlessly weeded out those not physically or mentally fit for the mission, and Wingate constantly exalted the importance of winning the war and warned his men that some would not be returning alive. Interestingly, rather than lowering morale this actually increased it. Gradually, the brigade welded into a seven column fighting force totaling over 3,000 men with mules, oxen and elephants to carry heavy supplies.

THE MARCH IN

On 12 February 1943, at the threshold of battle, Wingate addressed the men under his command, saying, “Today we stand on the threshold of battle…It is a small minority that accepts with good hearts tasks like this that we have chosen to carry out. The time of preparation is over, and we are moving on the enemy to prove ourselves and our methods. We need not, as we go forward into the conflict, suspect opportunity of withdrawing and are here because we have chosen to bear the burden and the heat of the day.” With this “Operation Longcloth” began and the 3,250-strong Chindits headed into the jungles of eastern India.

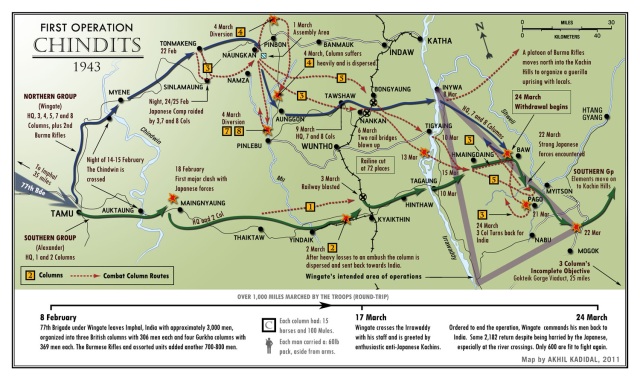

Two nights later, as a diversionary attack by the 23rd Indian Division struck Kalewa, two Gurkha columns under Lt-Colonel Leigh Alexander (a first-class Cricketer before the war) slipped crossed the Chindwin 50 miles to the south. Their mission: to attack Japanese outposts, blow up bridges and sever the Mandalay-Mytikyina railway at the key Burmese town of Kyaikthin. At the same time, Wingate, with five columns led by Lt-Colonel S. Cooke, crossed the river a little to the north and went forward to sever the same railway between Wuntho and Indaw. (see map above)

Wingate’s main objectives were to:

1) Cut the main railway line between Mandalay and Myitkyina

2) Harass the enemy in the shwebo area

3) Cross the Irrawady river and cut the rail line between Mandalay and Lashio

The operation called for extraordinary ability and luck. The first objective was 150 miles to the east with the number one priority being to reach the target undetected.

In an effort to break the formal regimental structure of the British Army, the seven columns each had about 400-500 men, 100 pack-mules, horses or oxen and accompanied by RAF radio operators, under the overall command of Squadron Leader Robert Thompson. Each man in the lightly-armed columns (heaviest weapons were medium machine guns and mortars), had to lug a 70 lb (31 kgs) load, including a pack, rifle, bayonet, ammunition and grenades, water bottle, four pairs of socks, spare shirt, climbing rope, utility knife and a five day ration pack consisting of biscuits, cheese, chocolate, meat, nuts, raisins, dates, tea, powdered milk and sugar. All together a daily ration weighed less than 1 kg (2 lbs) – although these meager rations were sometimes augmented by local bananas, rice and other fruits provided by friendly villagers.

As men marched, others struggled to get their mules over steep and plunging ridges. Burma was the land of extremes, rich with ancient cultural architecture and a treasure of natural resources amid lush rain forests and hills. Yet northern and central Burma was no tropical paradise. Mountain ranges thick with seemingly impenetrable jungles covered the borders. The rain forests were trackless, steep regions, filled with vines and rotting vegetation. This, alternating with sharp elephant grass as tall as a man or with thick bamboo thickets could obscure visibility to only a few meters. The steep hills and ridges provided narrow paths. The British depended on RAF (Royal Air Force) reconnaissance and Burmese guides to get them through. Summer humidity reached up to 46º Centigrade (115º F) in the central plains, and during the monsoon, which lasted half a year, pack animals became the only reliable form of transport in the narrow jungle trails and through the mud. In this pitiless environment the Japanese became only one of the Chindits’ many enemies.

There was the torrential rain, for one, which produced a sea of glutinous mud and permanently sodden clothes, and the dense thickets of brush and foliage which slashed at men and animals. “Sometimes the going was frightful, occasionally it was just bad,” said one man, Sergeant Tony Aubrey. Like many Chindits, Aubrey was astounded by the scale of the Burmese jungle, the constant dew and rains which wet uniforms and equipment, the oozing black mud, belligerent red ants and huge black spiders with their painful stings and thickets of impenetrable bamboo whose stalks and leaves “cut both clothes and flesh to ribbons.”

Clothing, boots and skin rotted from prolonged exposure to the humid atmosphere, and the first casualties from tropical and parasitic diseases were reported. To this were added swarms of leeches, clouds of mosquitoes which appeared regardless of the time, poisonous snakes, flukes, ticks and flies. Open wounds were to be quickly covered up or risk viral infections. Many of the Chindits quickly learned that wearing beards (like Wingate), mitigated the need for a shaving kit, formed the best natural camouflage for the face, and more importantly – kept out mosquitoes and ticks.

Progress was painfully slow but Wingate tried to hasten the advance by paying surprise visits to subordinates and issuing radio orders embedded with Biblical quotations. By the beginning of March, Cooke’s group was positioned at attack the railway. Meanwhile, in the south, Alexander’s two columns were advancing without incident. Every day, British C-47 Dakotas from 31 Squadron and the Lockheed Hudsons from 194 Squadron appeared over pre-arranged drop zones identified by accompanying RAF signalers, dropping supplies. On March 2, the No. 5 Column led by Major Bernard Fergusson brushed aside a Japanese patrol and blew the bridges at Bongyaung, the cracks of the explosions ringing through the hills. The attack had taken the Japanese completely by surprise, but they recovered and two divisions were dispatched to deal with the intruders who were believed to be no more than a reconnaissance party. In the south meantime, Alexander’s columns had been heading down to the Irrawaddy River. Moving in force, Alexander hoped to create the impression that his columns were the vanguard of a larger British force. The Japanese called his bluff and attacked, badly mauling No. 2 Column.

By now convinced that an entire British commando division had crossed the Chindwin, the Japanese Army spent several tense days scrambling a counter-offensive. But misinformation and speculation plagued their understanding of the situation. Most Japanese commanders were even baffled at how this “commando division” was being supplied. They simply could not or would not believe that the British would be so brazen as to resupply their forces in full daylight with slow and vulnerable transport aircraft – especially in an area heavily patrolled by Japanese fighters.

In the north meantime, things were going better. Of Cooke’s five columns, three moved north with the intent of drawing Japanese forces away from other two columns heading to hit the railways. The diversionary force soon met the enemy at the Irrawaddy. One column (Major Bromhead’s No. 4 Column) was badly mauled and scattered, forced to withdraw back to the Chindwin. Yet, 4 Column’s sacrifice had not been in vain. Two other two columns – Fergusson’s No. 5 Column and Michael Calvert’s No. 3 Column – were able to use the confusion of the melee to move unobserved to the railway line and adjacent bases. They reached their positions in early March; to sabotage the line in 72 places, destroy bridges and cut roads.

As Japanese awoke to the threat, the Chindits set up ambush parties and waited for the Japanese as they rushed to respond. Hundreds of Japanese were wiped out and pinned down by the ambush parties even as Fergusson’s and Calvert’s RAF signalers called in RAF air support to complete the massacre. Elated at these early successes, Calvert pushed on to destroy the Gokteik Gorge viaduct, an important structure which carried the Lashio road about 100 km (60 miles) north of Mandalay. But now the columns had to cross a triangular area between the Irrawaddy and the Shweli rivers – an area that was open, waterless country, criss-crossed by roads and frequently patrolled by enemy armored cars. It was hopeless for guerrilla operations.

THE RETURN

As the unfavorable terrain and Japanese commitment escalated, the expedition began to unravel.

The hardships multiplied when supply drops became difficult, not only because of Japanese fighter patrols, but also because by now the Chindit columns had become so dispersed that air supply had become all but impossible. This in turn increased the demand for food and water. Many columns struggled, if only for a few hours to keep ahead of pursuing Japanese forces while hurriedly collecting supplies from airdrops. Others fought for the supply zones and villages where the Japanese stationed troops knowing full well that the Chindits would seek them out for food. Finally in desperation, men ate many of their mules and made a soup of their horses.

Informed of the situation, Lt-General Geoffrey Scones of the British IV Corps, ordered Wingate to withdraw. Wingate in turn instructed his columns to disperse in small, independent parties on March 24th. Lt-Colonel Alexander’s group shifted to the east, hoping to reach the safety of China while Cooke’s group fell back to the Irrawaddy. The men were now exhausted and riddled with disease. Sadly, many of the wounded were left behind. Lieutenant Ian MacHorton of No. 2 Column was one of those abandoned. “At the moment when I gave up straining my ears for any last faint sound of my vanished comrades, my utter loneliness engulfed me,” he later wrote.

One by one, small groups of Chindits struggled through the jungle and managed to cross the Chindwin. Wingate returned to India on April 29. Fergusson and Calvert also made it, but some 883 were lost, killed, wounded or captured – many as they crossed the Chindwin, where Japanese patrols were waiting. Of the 2,182 that did return, only 600 would ever fight again. They had spent almost nine weeks in the jungle and had marched over a thousand miles, and Wingate regarded the entire operation as a bitter failure.

But how key had their efforts been? In February, before “Longcloth” was launched, Wingate had told reporters that, “If this operation succeeds, it will save thousands of lives. Should we fail, most of us will never be heard from again. If we succeed, we shall have demonstrated a new style of warfare to the world, bested the Jap at his own game, and brought nearer the day when the Japanese will be thrown bag and baggage out of Burma.” Disregarding the little material damage inflicted, in which some railways were cut, bridges blown or Japanese killed, “Longcloth” had accomplished ten times its weight in psychological terms. In one blow, the Chindits had destroyed the myth of Japanese invulnerability, and showed that a lightly-armed, well-trained force could take on the Japanese, beat them at their own game, in their own backyard and return to talk about it. At a time when heroes were badly needed and when the Allies faced their darkest hour, Wingate and his Chindits were indeed heroes.

The tales of their endeavors ran like a hurricane through the dispirited armies in India. Newspaper articles carrying photographs of a gaunt, bearded Wingate in an Australian slouch hat and his battered Chindits only strove to increase the legend. A copy of Wingate’s after-action report reached the Churchill, perhaps the final judge of success. Depressed by the long string of defeats and disappointments in the Far East, Churchill was jubilant to hear of Wingate’s success.

In July he wrote, “I consider Wingate should command the army against Burma. He is a man of genius and audacity, and has rightly been discerned by all eyes as a figure quite above the ordinary level… There is no doubt that in the welter of inefficiency and lassitude which has characterized our operations on the Indian front, this man, his force and his achievements, stand out, and no mere question of seniority must obstruct the advance of real personalities to their proper stations in war.” So impressed was Churchill that he wanted to Wingate promoted up four ranks, over the heads of other senior men. The proposal was met with shock, and then resistance from senior army commanders.

In the end Churchill had to settle for promoting Wingate up one rank, to Major-General. But tellingly, he insisted on taking him to Quebec for the Allied Quadrant Conference that August. Here, Wingate won approval for an expanded Chindit force and a more ambitious expedition that following year in cooperation with U.S. Lt-General Joseph “Vinegar Joe” Stilwell and his Chinese Army. Many Allied officers seethed at these concessions, not least of all “Vinegar Joe,” who having waited long and hard for U.S. troops became enraged when told that the 3,000-strong American Regiment, nicknamed Merrill’s Marauders, was being diverted to Wingate’s command.

“After a long struggle we get a handful of U.S. troops and by God they tell us that they are going to operate under Wingate,” Stilwell said. “We don’t know how to handle them but that exhibitionist does! He has done nothing but make an abortive jaunt to Katha, cutting some railroad that our people had already cut, get caught east of the Irrawaddy and come out with a loss of forty percent. Now he’s an expert. That’s enough to discourage Christ.”

Yet, barring his critics, great things were expected of Wingate — now that he had been reinforced, and as 1944 came, his legend and that of his beloved Chindits multiplied as they went into the task of completing all that was asked of them and more. But that is another story.

—————————————————————————————————————————-

Acronyms & Abbreviations:

Bn – Battalion (In British Army, the basic combat unit capable of independent action)

CO – Commanding Officer

KIA – Killed in action

KIFA – Killed in Flying Accident

RA – Royal Artillery

RAMC – Royal Army Medical Corps

RE – Royal Engineers

Regt – Regiment (In the British Army, purely an administrative term)

RIAMC – Royal Indian Army Medical Corps

RIASC – Royal Indian Army Service Corps

WIA – Wounded in Action

—————————————————————————————————————————-

—————————————————————————————————————————-

Sources:

For a full bibliography of all Chindit writing on this site, check the bottom of this post: Chindits – In 1944.

Can I please have your permission to use the map on this section of the Chindits, 1943? I hope to use it in my printed transcript of my father, Capt T.C.Roberts’ POW diary, which I am producing privately for the family, as part of my late father’s legacy.

Many thanks

Patricia Ireland

My father Sgt Sam Quick was a POW,held in Rangoon Gaol for 2 years.He was part of the 1st Chindit expedition.He was from the Kings Regiment(Liverpool)He survived & died at the age of 86 in 2001.His best friend (Bob Glasgow-from Edinburgh) was wounded & had to be left behind with a few rifles& grenades.

He started to write his memories at my request but never finished.

Regards

Tony Quick(DOB 4/4/1940)

The Rank chart is a modern one. The St.Edwards Crown wasn’t used in 1943, but from 1953 on, by Queen Elisabeth II.

Why, you’re absolutely right, old chap. The Tudor Crown is required.

Anyway, the image has been fixed.

My father pte Henry Taylor 13th Kings was interviewed by me some years ago on his experiences in a group of 12 who tried to walk out.

Only 6 managed to make it in June. The interview was archived at the

British Museum and is available although not cheap if anyone is interested

Pingback: War stories…. World War Two edition (2) – The Knife and me

I have a Chindits patch in my collection and having a hard time finding information about the patch. Was told it’s a pocket patch but I can’t find any pictures of a member wearing this patch? Has the Chindits name above the figure. Came out of an old collection. Would like to send a few pictures of the patch

Hi, Keith. You can send images if the patch to akhil213@yahoo.com. I will take a look.